10.06.2025

Open Wide, It's All In Your Head

Herein, a subject we’ll all meet up with.

We meet up with it at an early age, and no matter how diligent one is, it’s a fact we will meet up with it on a regular basis for pretty much the whole of our lives. Around twenty percent of the population fear this meet up. They fear it to the extent they’d rather suffer other ‘unsavoury’ consequences in order to avoid this service, which also, by the way, has the proven added benefit of extending the human lifespan. Some people allow years to go by without the service, while many others stall on setting appointment dates, postponing the inevitable by use of this, that, or some other sad excuse, telling themselves they need only a little more time to summon the courage.

If having avoided the service, and a large helping of luck is with you, then it won’t be mid-Saturday evening when, either by subtle recognition, or in a shocking instant—while chewing almonds, ice, or pork crackling—you become the centre of attention in your own enamel emergency.

The throbbing punctuates all one’s thought and action, and is about as welcome as that bastard neighbour’s leaf blower. You are as ready as ever to launch yourself into that firm padded chair, reclined to face the ceiling, and shone on by a brilliantly bright lamp. Throb, throb, throb goes the jawline. Pang, pang, pang goes the tooth. Your dental surgery is imminent. You open wide, and with your tongue, point to the offending tooth: ith waan!

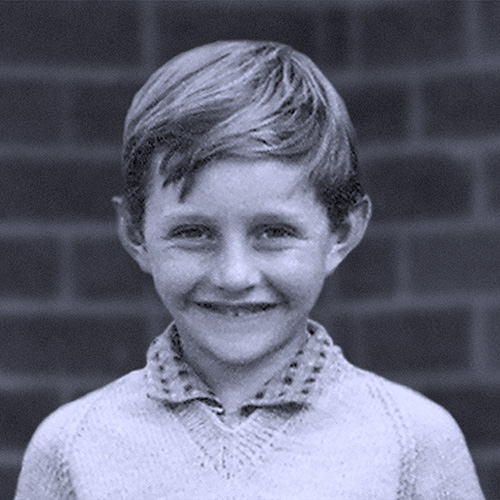

Dentophobia, or odontophobia, the fear of dentists, is perfectly understandable, especially if you, as I, became familiar with dentistry processes in the previous century. In my case it was around 1967. Fortunately, this was in the period after dentistry had also been a legitimate professional sideline practiced by barbers...as well as by toothless spinster aunts—their own teeth replaced with dentures, standard practice back then—using what ever devices were to hand—leather working tools, anyone?

How it was that I came to have my choppers worked on for the first time remains a mystery. It can only be assumed a communication was handed me at school, to deliver to my parents, informing them the government mobile dentist would soon be pulling up, my attendance required on such and such a date.

For my part, what, if anything might have been anticipated about a dentist visiting my primary school, has flown the memory. But ever since that episode, near to annually, ‘dentist day’ is informed by a replay of those original images, sensations, and tastes. The yuletide rewatch of It’s a Wonderful Life, it most definitely is not. There is no angel tinkling the happy bell each time a tooth goes to heaven. Of course, there is, too, that scene in Marathon Man. What there is is the gross recollection of the tamping down into the hollowed out gnasher cavity of the amalgam filling, its texture a kind of squidgy metallic substance that almost squeaks as it is pressed in, the resultant sensation a salty dull electric current, like that of the tongue meeting the contacts of a nine-volt battery. But I get ahead of myself.

There first came the small room where procedures are conducted. I hesitate to use the word surgery because it being on wheels, and fabricated of ply-wood, it did not present well. Even back then, sighting it for the first time, something told me it was weird! My memory might be a little off on this count, but shock at the sight of the dentist’s mobile place of operations has me recalling the dentist appearing the same broad squat shape as the rotundity of the dental caravan itself. Below is an approximation of that damned drilling rig. The corresponding physique of DENT-O-MAN and his spit wagon are indelibly etched, just as the scrape of his dental scaler. Even now, my toes curl. Toes, by the way, would eventually aid in mitigating future dental tribulations.

Having seen the exterior view of the van and bearing in mind your own understanding that there are sundry cabinets and drawers, there is, bolted to the floor, the central apparatus: the dentist’s chair, with its ability to be reclined and, therefore, to use up even more of the van’s limited space. There is the power tower, which facilitates operation of the dentist’s hand-piece, and also supplies irrigation and cooling of high-speed cutting, grinding, and polishing tools, while a suction tube vacuums fluids from the agape patient. We have the rinse-and-spit basin, and the dentist’s critically important stainless steel probes arrayed on a dainty paper placemat, set upon the surgical instrument tray…the quiver of shiver. I ask you, try and visualize this crammed interior being towed, bouncing over ‘60s rural roads, motoring from one primary school to another, dentist and nurse on the bench seat of a sedan, while youngsters trembled in their classrooms awaiting their turn… Is this not the image of a torture chamber on wheels?!

The van was parked within the grounds of the school in line of sight of its three classrooms. There were more than a few faces pressed up to the windows observing the comings and goings from the little van of hurt. Their faces were the full scheme of human nature, from tenderness to callousness; sad eyes and crazy faces. As in dreams, and nightmares, one moves through time and space where interstitial events seem edited out. And so it was that at a particular moment I found myself standing before the open door of the capricious caravan of horrors, its antiseptic scent wafting as the smiling dental assistant appeared, ushering me now to step up, for I was next.

Some time in the nineties I’d read in Barry Humphries’ autobiography More Please, that his teeth and his life with them as a youngster was an intimate distress, made worse by them being attended to by of all things, a family relation—elderly—and made worse in the telling, in that it was somehow connected to a train trip to a holiday in the country. Thinking on it, I can only wonder if by chance Barry’s childhood dentist might have been among a group of hold-outs to the end of their era; the last of the last barber-dentists, more acquainted with honing, stropping, and wielding a straight razor. I wonder also what may constitute a dental scene in a tale of science fiction, if Little Shop of Horrors doesn’t meet the criteria. I imagine space dentistry in Star Trek—on TV, contemporaneous with my dental experience of 1967—Gene Roddenberry’s Starfleet personnel aboard Enterprise on the ‘grooming’ deck, let’s say, in to have their bangs and bicuspids done in the one appointment.

The tale told here is in anticipation of returning to my present-day dentist for part two of a crown procedure, the Right First Molar. In part one, the tooth requiring attention—which had been attended to well over a decade ago and had its nerve silenced after the broken and cracked parts had been replaced with new work to protect the small part that remained—was now showing signs of an imminent catastrophic WTF (Whole Tooth Failure). In an earlier routine clean and check-up, I was warned by my lovely and efficient dental hygienist: “You’ll need a crown.” My first thought was: Yeah, I wish I had one—a crown—so I could prise a ruby, or sapphire from it to sort the bill! Confessing to the genuine excuse of delay, I put it off a few months. The consolation was the knowledge that I still had in my possession a powerful analgesic—safely secreted after an appalling kidney stone event—which I could avail should my ticking tooth time-bomb hiss into life mid-weekend as my dentist would likely be dining aboard his airship over a central Australian sunset.

Cranebrook Public had sunshine falling upon it that morning. I cannot say it was reflected in my disposition. I was in the chair, and the hefty bespectacled dentist was going to work somewhere on the lower right. Whatever pain there was vibrating directly via the jaw and sonically through the air of the grinder in those close quarters is no longer acute in any recollection. Best it be so. There was an injection that got the whole thing started, but it plays no part in recalling the overall experience. What is most remembered is the beginnings of my learning to transmute anxiety while in the recliner. The only freedom of movement outside the mouth was of fingers and toes, and since the toes were furthest from the teeth and gums, the games of playing rhythmic toe piano inside my black socks and shoes, permitted a kind of escape.

Some time later, in the ’90s, a dentist offered me the opportunity, via reflection in a hand-held mirror, the observation of my own root canal procedure. The first thing one notes is just how much smaller all the goings on are, how much the imagination inflates.

After all it really is all in your head.

TA

Sci-Fi dentistry. Research turns up various informative and entertaining notions:

https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Dentistry

P.S. I'm working on my next book, and if you'd like to keep up with how it's progressing, and the clever manner in which I make excuses for the 'occasional' distraction, head to Books -> FtB.